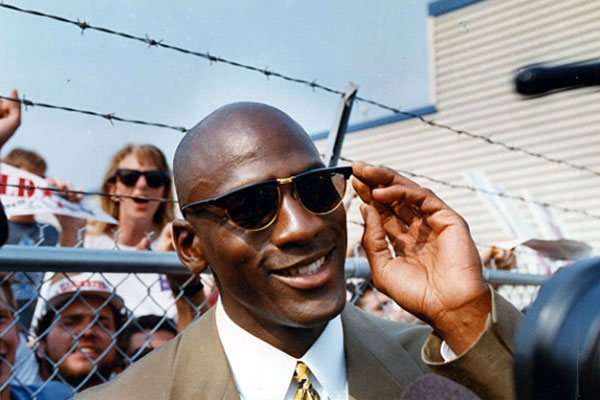

Picture this. Twelve guys are moving across a basketball court. Eleven run backwards—concentrating on their feet, or peering over their shoulders, as if worried that someone has placed ottomans in their paths. At the end of the line, one man trots straight ahead, face forward, his eyes averted as if not to embarrass his teammates by paying the slightest attention to a drill he doesn’t need. Eleven guys skip sideways, back across the court hopping like girls making fun of one another. At the end of the line, one man trots straight ahead, face forward. Eleven guys are dressed in motley conglomerations of sweat shirts and pants, but all wear the reversible practice jerseys of the Chicago Bulls, some white side out, some red. One player doesn’t bother with the practice jersey. When the team separates into two opposing practice squads, no one is going to have any trouble remembering which team that player is on

There is a player like this on every team in every sport around the world, a guy who doesn’t bother with what he doesn’t have to, and Michael Jordan has probably been that player on every team he ever played on.

Michael Jordan can do this because Michael Jordan can do this:

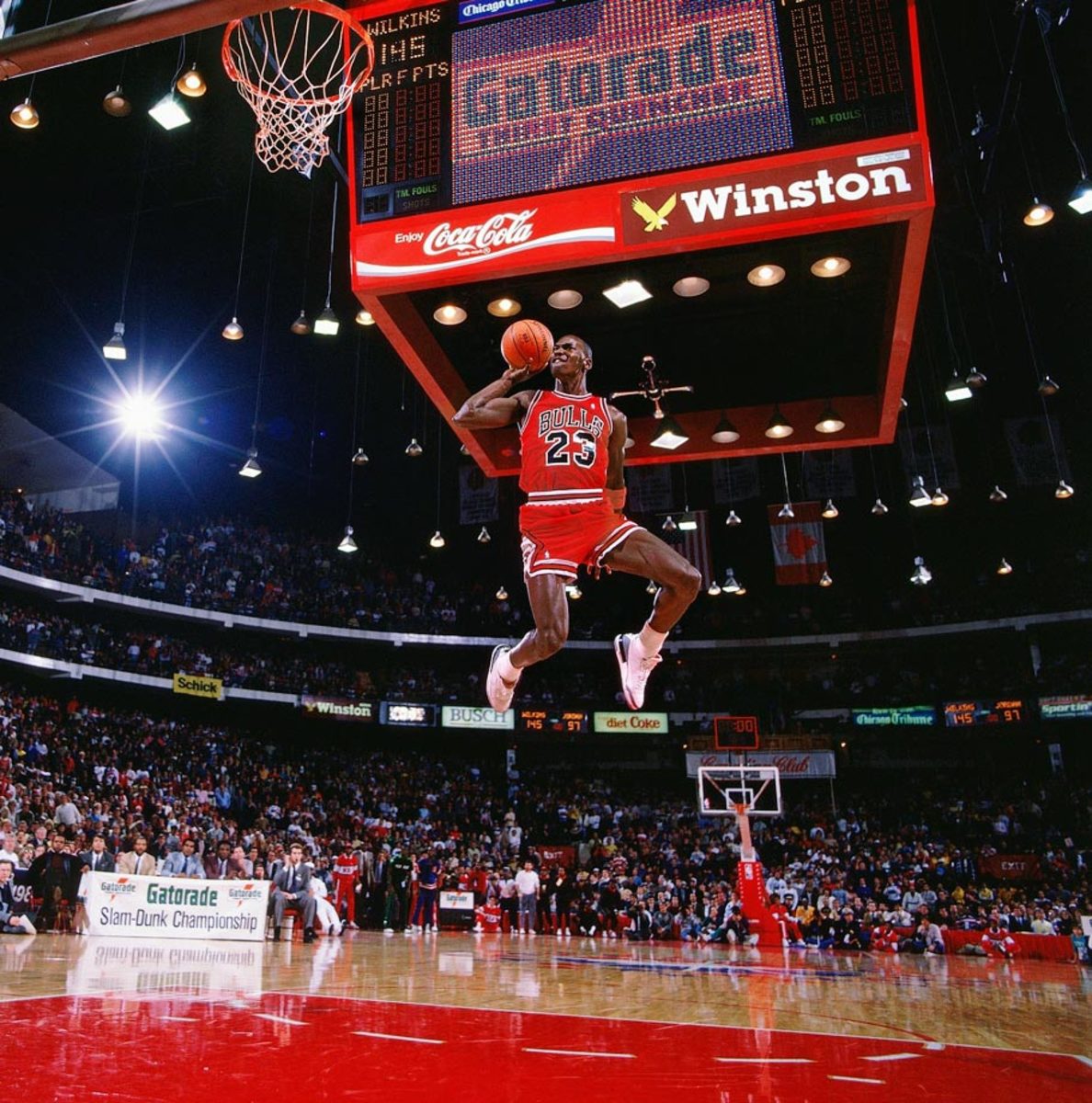

- He steps in front of an opponent’s pass and is gone, down the sideline, and closing on the hoop he rises, feet apart, pumps the ball once, twice, and then jams it in as if trying to get it through without the hoop’s noticing. Three of the opponents don’t even move from their spots upcourt. After a moment’s pause two others jog back—someone has to—in Jordan’s wide and considerable wake, to take the ball out from underneath the basket.

- He is double-teamed and trapped along the base line. Cutting around the center to lose them, he shimmies like a boy going through a gap in a fence, leaps again, and with one hand slams the ball through the hoop.

- On defense again, playing about five feet off the man he’s guarding, he jumps like a puppet jerked by its string. His arms flail up and his hands close upon the basketball as it passes. overhead, as if it were the most amazing piece of luck in the world.

- In overtime, screaming as he dribbles near the free-throw circle, he orders his teammates to spread out to the corners of the court, then moves in with the staggered rhythm—quick, then slow, lurching, then erect—with which he both intimidates and hypnotizes his opponents. He fakes with his shoulders one way, moves to the free-throw line, fakes three times quickly to rock the man back on his heels, then leaps and, from a moment of stillness, shoots. He is on his way downcourt, his back to the basket, as the ball rattles off the back rim and through the hoop.

- While driving in, as three opponents leap to block the expected dunk, he releases the ball with fingers spaced wide, as if he were freeing a dove. It rises as of its own volition up, off the backboard, and through the hoop.

In short, Michael Jordan can do things no one else can. Yet ask him how it is he does these things and he is apt to say, “I try to be creative,” or “It just happens,” or “It just comes to me.” Playing basketball is, for him, a creative process, and he seems reluctant to discuss it. If writing is, as E.B. White explained, the art of bringing down thoughts on the wing, Jordan desires a way not of bringing down those thoughts, but of becoming them as they fly.

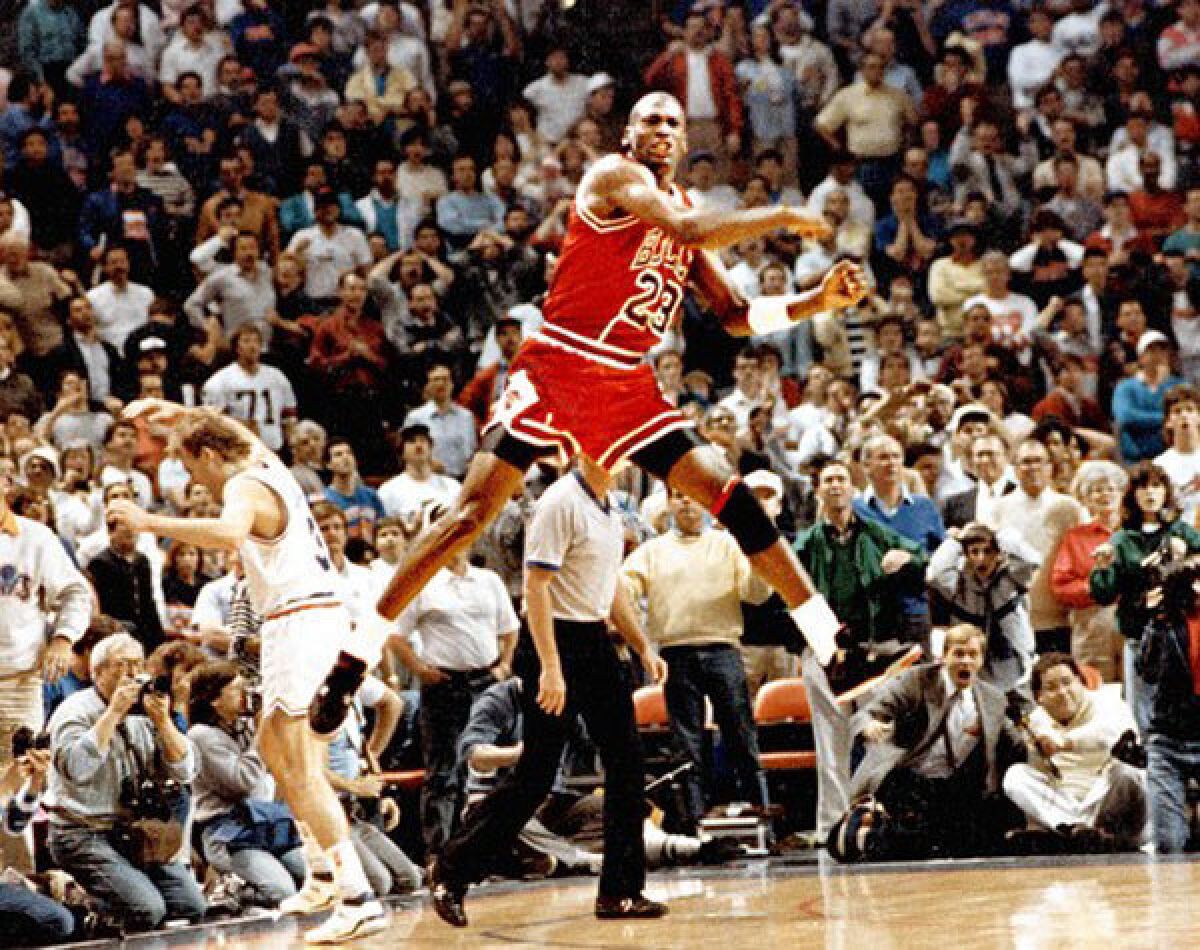

He is the reigning Most Valuable Player of the National Basketball Association, winning the award last summer for a season in which he became the first person to lead the league in both steals and points scored. He stands out as the most arresting and, not coincidentally, the most marketable player in the sport. He outscores his closest competitor by more than five points a game—500 points over the course of a season. He is, by himself, a one-man team, clearly deserving of the MVP award; but in a league that is evolving toward deeper, more balanced play, he is something of an oddity—almost an albatross. How can a player so good treat others as equals? How can a player so accomplished be simply a member of a team?

For Jordan, there is another question equally important: How can he win an NBA championship if he isn’t?

Michael Jordan is an owner’s dream true: He is guaranteed to put fans in the stands as long as he stays healthy. The Bulls, who drew 6,000 fans a game as recently as 1984, before Jordan’s arrival, now have a waiting list for season tickets. The Chicago Stadium is packed 17,000 strong for every game. Yet for that reason he offers certain problems to Jerry Krause, the Bulls’ vice-president for basketball operations. As a guard, handling the ball much of the time, Jordan is both in the fans’ eye and at the edge of the team’s offense. No team with Michael Jordan is ever going to be so bad that it qualifies for one of the top picks in the college draft, yet no team dominated by a single player as the Bulls are dominated by Jordan is likely to win an NBA championship.

During the 1985-86 season, when Jordan was injured, it appeared the Bulls would fail to make the playoffs, and thus qualify for a shot at drafting center Patrick Ewing out of Georgetown. But Jordan returned in brilliant form and rallied the team into the last play-off spot-and out of a center. Meanwhile, the eight-year, $25-million contract he deservedly signed last year has put certain constraints on the Bulls’ chances for improvement. The league’s per-team salary cap prevents Chicago from snaring another high-priced star.

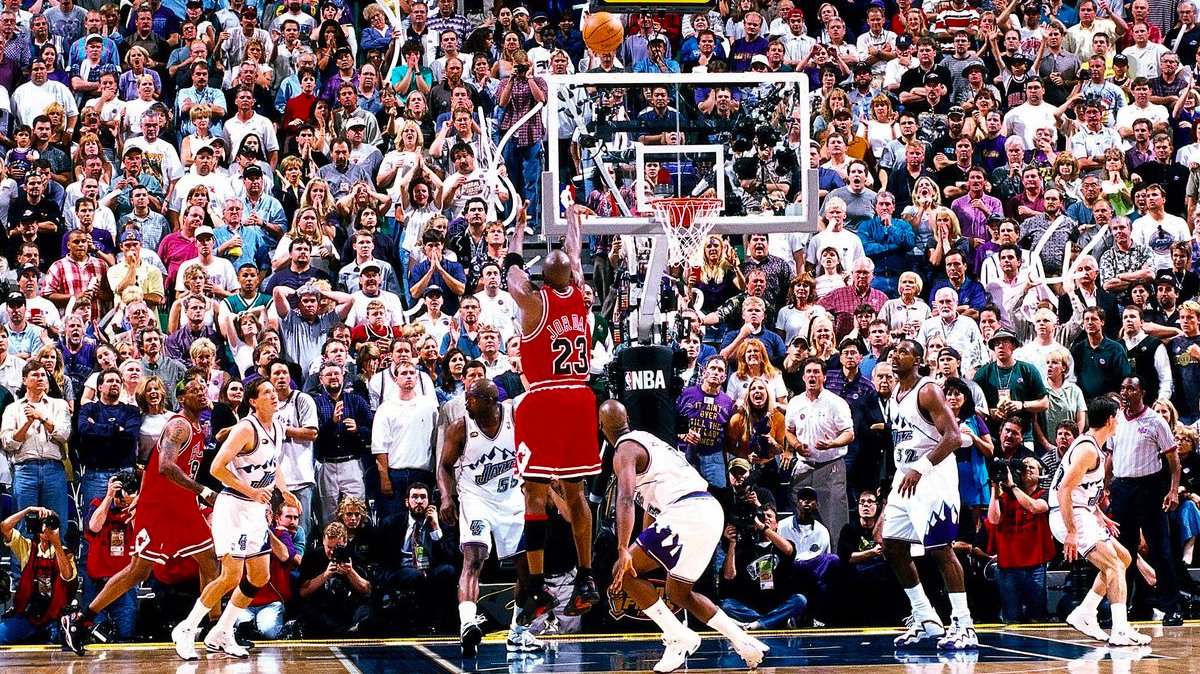

And exploiting Michael Jordan’s talents has become more difficult. Nowadays when he finds himself suddenly open, with no one between him and the basket, it’s not because he simply stumbled into the situation. When Jordan breaks free, more often than not it’s because of a pick set by the center, or because the man assigned to guard him was rushing to block an apparent outside shot by the other guard, or because of some intuitive pass—somehow on the same level as Jordan—that found him open just at the one moment the defense had neglected him. When Michael Jordan is closing on the basket, about to perform some move not even he himself has yet envisioned, it is because of the efforts of some one or two or three or even four members of his team. This year, more than any other during Michael Jordan’s tenure with the Bulls, the team is responsible for Jordan’s success almost as much as he is responsible for its success.

Last year, the team’s success was considerable. The Bulls won 50 of their 82 games for the first time since the days when Dick Motta coached Bob Love and Chet Walker, Jerry Sloan and Norm Van Lier, 15 years ago. They did so with a team that was geared to get the ball to Jordan and, for the most part, to Jordan alone.

Yet for the Bulls to remain at the same level would have been to fall behind new, developing NBA powers in Cleveland and New York, recently infused by college talent in the person of Brad Daugherty and Patrick Ewing, both large, dominating centers. In addition, the league’s elite teams have been in transition in recent years from star-dominated offenses to more team-oriented, balanced offensive and defensive play, with the rise of the Detroit Pistons serving as the most noticeable example. The Bulls could have entered this season as they left last season: knowing that the team would win most of the time, that Jordan would capture another scoring title, that the Chicago Stadium would be filled with ever-more-opulent fans, but that the team would lose when Jordan had an off night, or when-in the play-offs, for instance-his best simply wasn’t enough.

So the Bulls decided to diversify. Yet in moving from a specialized to an egalitarian style of play, each player—Jordan included—encountered new roles. A good basketball team operates almost instinctively, naturally, and the Bulls have had to ingrain that new way of doing things.

Jordan and his band now embrace more complex structures in their rehearsals. His unique dribbling style and scoring ability remain captivating. Despite rumors, Jordan saves his dunking for games. The Bulls seek better balance by adding a quality center to complement Jordan’s talent. The center position has been historically weak for the Bulls, but Bill Cartwright brings hope. Cartwright’s arrival was an astute move, addressing a key area of improvement. The team chemistry is crucial, and the Bulls have worked to build a cohesive and quality roster. Horace Grant and Scottie Pippen hold promise as young talents for the future. While Jordan’s greatness is evident, the team’s success depends on finding a balance between his dominance and the collective effort of the players.