If Sergio Aguero’s birth had been arduous enough for his parents, naming him proved almost as difficult. Adriana and Leonel had wanted to give him the middle name Lionel, but Buenos Aires’ list of approved names only contained ‘Leonel’, meaning the youngster had to settle, just as his father had done 20 years beforehand, for a different spelling.

That was not the only problem they had. Although he now goes by the name Sergio Leonel Aguero Del Castillo, only his mother’s surname, Aguero, appears on the birth certificate. Argentine law considered both Adriana and Leonel minors at the time of Sergio’s birth, and as they were also unmarried, only the mother was allowed to be recorded as a parent.

Adriana and Leonel tried to rectify this four years after Sergio’s birth, but they needed perfect copies of their national identity documents. They had been lost in the floods that so nearly led to Adriana losing her first son, and the issue has never been officially rectified.

Credit: Born to Rise

But no amount of South American bureaucracy can rob Sergio’s parents of the satisfaction of knowing their decisions and sacrifices allowed their son to reach the very top.

Two years after his first appearance at El Rojo’s Doble Visera stadium, the Argentine press began to take notice of Kun, with a report in Cronica highlighting him as “a player you could put your mortgage on going on to have a successful future”.

That was almost literally what one of Europe’s biggest clubs were willing to do.

“I believe that one of the most important points of Sergio’s story was his parents’ decision-making ability,” says Daniel Fresco, who spoke to virtually every significant figure in Sergio’s life while working on his official biography, Born to Rise.

“When he was barely 13 years old, Leo and Adriana were presented with a mind-boggling offer to sign Kun from Juventus. Even though they had already started to receive some monetary compensation from a local businessman who was investing on Kun’s potential, the family still had many needs. It was very hard to reject the offer.”

Yet reject it they did, and they soon decided, with the encouragement of investors Samuel Liberman and Jose Maria Astarloa, that Sergio would need more experienced representatives. At the age of 14 he was signed to international management company IMG, and advisors who look after him to this day.

The agreement with IMG also sparked the first of two whirlwind periods during Kun’s teenage years.

As well as providing the family with a new and bigger house, IMG helped the youngster sign up with Nike. Then, three days after his 15th birthday and in another kind twist of fate, he was fast-tracked to Independiente’s reserves by their new manager, a former youth coach he had impressed years earlier.

Within a month Sergio would become the youngest ever player to appear in an Argentine Primera Division match.

“It all happened very quickly,” is the best way Aguero, speaking exclusively to Goal, can explain it now.

Within a fortnight he found himself making up the numbers in first-team training. The next day he played for the reserves, and the day after that he played against the first team in a training match. It was then that he was asked if he wanted to be on the bench for the next league game, against San Lorenzo.

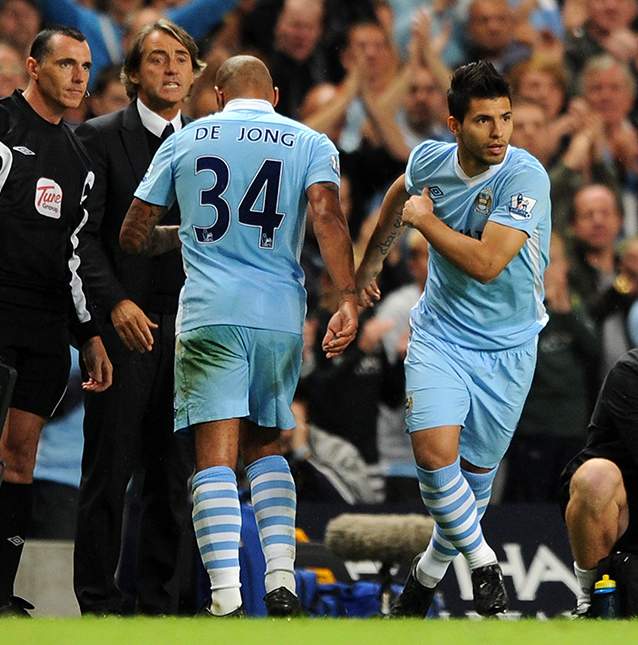

Of all the coincidences and quirks of fate that have marked Aguero’s career, there is one that he remembers particularly fondly: “When I debuted here at Manchester City, I had the No.16 shirt and I came on for Nigel De Jong, who was No.34,” he says enthusiastically. “When I debuted at Independiente, I had the No.34, and I came on for the guy who had the No.16.”

Pablo Zabaleta, now a close friend of Sergio’s, was in the San Lorenzo team that day, while the game was also Independiente hero Gabi Milito’s final appearance for the club before he moved to Europe – similarly to how the first game Sergio attended as a fan was the final game Hernan Crespo played for River Plate before moving to Parma.

Yet perhaps the most interesting detail about Sergio’s debut is that it was watched on television, 300 kilometres away, by a young Lionel Messi. Not ‘Leonel’ Messi, you may have noticed; authorities in Rosario did allow the ‘Lionel’ spelling, meaning the Messi family did not have the same problems as Sergio’s parents. Spookily, however, Jorge Messi had actually intended to call his son ‘Leonel’, only for a mix-up during the registration process.

Messi, having already moved to Barcelona, was back in Argentina on holiday when he saw Aguero make his record-breaking debut, something which has stayed with him forever.

“I know for a fact that Sergio and Leo share a close bond,” Fresco, who interviewed both men countless times while writing Kun’s book, adds.

“The thing that had given Messi the most lasting impression was watching a game on TV where he heard the narrator proclaim it a historic day, that the youngest player in Argentine Primera Division history would set foot on the field at only 15 years of age.

“He didn’t quite catch the name of the kid then, but Leo did find it uncanny that a boy so young would be playing professionally.”

Despite that remarkably early debut, Sergio’s club career would stall somewhat, with a rocky period for Independiente ensuring he did not make another start for almost a year. But three consecutive games – and his first ever goal – under Pedro Damian Monzon, El Rojo’s sixth coach in 18 months, and then a run under their seventh, Cesar Luis Menotti, earned a call-up to the 2005 Under-20 World Cup in the Netherlands, where he would forge a lifelong friendship with Messi.

Messi celebrates after scoring at the 2005 World Youth Championships

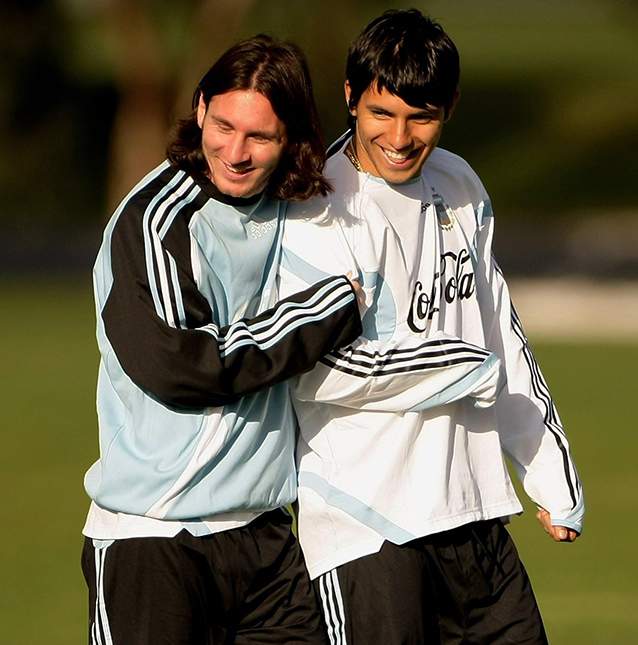

“They had already met, almost by random chance, earlier that year at the national team’s training camp on the outskirts of Buenos Aires,” Fresco adds. “Leo had been summoned for the U20 team and Sergio was playing for the U17s. Kun hadn’t met him before, but both of them had heard of each other. Sergio knew there was an Argentine teenager playing for Barcelona, who, according to the local press, had an extraordinary career ahead of him.

“He wasn’t able to put two and two together until that meeting – “who are you?”, Sergio asked him. “Messi”, was all Leo replied. The other kids told Sergio he was playing for Barcelona.”

Messi, of course, had already seen Aguero in action.

Fresco adds: “Leo wasn’t able to figure that out after their first meeting either, but Leo and Sergio shared a mutual admiration even before they’d met.”

They were the two youngest members of the Argentina squad that travelled to the Netherlands, but it was not only for that reason that Miguel Angel Tojo, one of Argentina’s great youth coaches, decided the two should room together.

“Miguel Angel told Kun that he’d share a room with Leo because he believed Sergio was destined for Europe, and Messi’s experience in Barcelona would be of value to him,” Fresco adds. “It was there that their friendship became stronger.”

Messi and Aguero struck up an understanding on the pitch, but it was what the two would go through behind closed doors that really made a lasting impression.

Emiliano Molina, one of Sergio’s childhood friends who had also made it to the Independiente youth ranks, was involved in a serious car crash back in Argentina.

“Sergio and Emiliano had dreamed of the great things they could achieve together,” Fresco says. “It was a huge blow to Sergio, who was greatly worried about his friend and was constantly checking for updates from Buenos Aires. The Argentina staff tried to shield him in case the worst should happen; if it came to that, they wanted to be able to tell Sergio in the best possible way.”

One night, news reached the staff that Emiliano had died, and in a bid to break the news to Sergio themselves they turned off the wifi in the hotel. Somehow, certain rooms still had access.

“Sergio was still asleep, but Leo had woken up earlier and saw the news online,” Fresco says. “It would be Messi who’d tell Sergio that his childhood friend had passed away. The shock was intense.

“After breaking the sad news, they hugged and cried together for quite a while, supporting each other despite the anguish that gripped them. It was a very trying time, and I believe it made their relationship stronger.

“The way Sergio and Leo told me about that moment shakes me to this day.”

Argentina went on to beat Brazil in the semi-final and Nigeria in the final, sparking emotional celebrations from a team that had rallied around its two youngest members at their lowest moments.

It was particularly easy to warm to Sergio in those days, as the parents back on the potreros and his Independiente team-mates and coaches could attest.

Fernando Signorini, part of Cesar Luis Menotti’s staff at El Rojo between 2004 and 2006, sheds some light on the characteristics that won the youngster plenty of fans.

Menotti, it is important to point out, had led Argentina to their first ever World Cup in 1978 and was one of the most revered sporting figures in the country.

“Sergio was 17 at that point,” Signorini tells Goal. “I remember the squad were all sat in the middle of the pitch, and Cesar introduced himself to each one. Sergio clasped Cesar’s hand, in the informal way that young players do with each other, and cheerily introduced himself as “Kun Aguero”.

“I’ll always remember that because it was a shock to see, but it was also sweet, and it speaks to the picardía (a combination of mischievousness and cunning) that is a product of the potrero, where Kun was formed as a player.

“He’s a very loveable kid, because he has that very infectious smile, he’s tremendously charismatic. He was loved by his team-mates from the start, and by the fans too. Right from the start the fans began to worship him, and that still exists to this day.”

Sergio had made another impression on his coaches, too.

“It wasn’t long into the training sessions when Cesar said his famous phrase, which provoked mockery in the media at the time, that Kun was very similar to Romario,” Signorini says. “Over the years he has been proven right.”

But it was under another iconic Argentine coach, Julio Cesar Falcioni, that Sergio enjoyed his second whirlwind period at Independiente.

On August 7, 2005, he wore the club’s famous No.10 shirt for the first time. Nine months later he was an Atletico Madrid player.

Once again, he had seemed to pack in several years’ worth of achievements into an incredibly short period.

In his final season in Argentina he scored three goals in two games against arch-rivals Racing Club; in the first game he scored an all-time classic derby goal and revealed a “For You Emiliano” shirt, while in the second he sunk Diego Simeone in his first ever game as a manager.

He was still just 17, but had earned comparisons with Diego Maradona (who he starred alongside on a television show), appeared in Nike commercials and signed sponsorship deals with Gillette and Pepsi. He also attracted interest from the world’s biggest clubs.

“At that point, the second youngest player was 23, and most of the squad were around 30, so I got used to being with people who were older and it helped me mature very quickly,” Aguero says now. “Already at that age I wanted to experience life in a different way.”

Any major European club you can think of was linked with a move for Aguero but it was Atletico who had followed him the longest – since Menotti’s time in charge – and it was for that reason they were not put off by the fact he was just 17.

Sergio had got his first run in the team thanks to a combination of his own abilities and Independiente’s struggles, and it was no different when the time came to leave for Europe.

El Rojo’s financial situation was dire, and by the middle of April 2006 they had agreed to sell their most prized asset for €23m – a record fee for Argentine football and the highest amount Atletico had ever spent.

Sergio would move to Europe, on his own, at the same age his father was when the Aguero-Del Castillos left Tucuman for the outskirts of Buenos Aires.

Aguero saw out the 2005-06 season with his boyhood club, but was denied an emotional goodbye at the Doble Visera, where he had made his unofficial debut at the age of 11.

Already on four yellow cards for the season, he knew another in a game at Olimpo would rule him out of the final home game of the season, against champions elect Boca Juniors. He even asked the referee for leniency before the match, but after 40 minutes he picked up a soft booking, provoking desperate appeals and floods of tears.

It meant he would not be able to play in front of Independiente’s home fans for the last time, and defeat in the final game, away to Rosario Central, ensured his final weeks at the club did not fit with the fairytale nature of the rest of his early career.

Not that anybody in Madrid, or Manchester, could say it held him back.