The steamboat Arabia carried 200 tons of treasure when it sank in 1856.

Marking the outline of the Arabia; 45 feet deep and about the length of a football field. COURTESY THE ARABIA STEAMBOAT MUSEUM

“YOU DON’T HAVE TO GO into the ocean to find a shipwreck,” says Kansas City explorer David Hawley. “They’re buried in your own back yard.”

Hawley and his intrepid team have quite the incredible passion: discovering and excavating steamboats from the 19th century that may have sunk in the Missouri, but now lie beneath fields of farmers’ midwestern corn. “Ours is a tale of treasures lost,” says Hawley. “A journey to locate sunken steamboats mystery cargo that vanished long ago.”

In 1988, Hawley and his crew uncovered the steamboat Great White Arabia, which sank in 1856 a few miles west of Kansas City. The discovery yielded an incredible collection of well-preserved, pre-Civil War artifacts. Hawley, along with his father, brother and two friends, unearthed over 200 tons of items, the equivalent of 10 container trucks. Many of these artifacts, from shoes to champagne bottles, are on display at the Arabia Steamboat Museum in Kansas City. Its tagline is “200 tons of treasure.”

When designing the museum, inspiration was drawn from departments stores to see how the merchandise would have been displayed. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

While most rescued sunken treasure is heavily water damaged and covered in rust and barnacles, the cargo of the Arabia was in relatively pristine condition, about as immaculately preserved as the day she sank 160 years ago.

Now Hawley and his team are excavating another steamboat, again buried not underneath the waters of the Missouri, but in a field a few miles southwest.

The first mystery is, of course, how a boat that sank mid-river ends up buried in a field. The answer lies with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. During the latter half of the 19th century, the Corps of Engineers undertook projects to forcibly alter the shape of the Missouri River. The plan was to bring the banks closer together, and by narrowing the width of the river, speed up the current, making boat passage much faster.

Preserved fillings for fruit pies. (Photo: Courtesy of the Arabia Steamboat Museum)

One such place was near Parkville, a few miles north east of Kansas City. It was here in 1856 that the Arabia sank after hitting a snag of a sycamore tree, sinking in minutes. As the course of the river was altered decades later, the steamboat became preserved not under the muddy waters of the Missouri, but in a corn field.

Local legends grew of a sunken steamboat under the cornfield of retired magistrate Norman Sortor. Rumors said it was filled with gold, or hundreds of barrels of Kentucky bourbon. “The lost cargo of liquor made the Arabia famous,” Hawley says. “Many searched for the treasure believing it to have ‘aged to perfection’ in the oak barrels lost deep in the river mud. It wasn’t the booze that was of interest to us, but rather that boat sank quickly … and it was reported to be full of cargo.”

Even items as delicate as reading glasses were preserved immaculately deep underneath the field. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Along with his father Bob, younger brother Greg and two family friends—David Lutrell, a local construction expert, and Jerry Mackey, a restaurateur—Hawley decided to see if the local legends were true. In 1987 they started gathering clues from old newspaper reports and river maps that showed where the Missouri had once coursed. Using electronic magnetic testing and sample drilling, the team started to see if they could find this stricken treasure ship lying underneath a corn field.

“Learning was done as we went along,” says Hawley. “First one needed to learn to research, then use a metal detector, then run equipment.”

By the autumn of 1988, the team had not only located the steamboat, but traced the outline of its main deck in the soil. It appeared that the Arabia occupied an area about the length of a football field, but was located 45 feet underground. The land owner gave them permission to dig, but with the proviso that they were out in time so that he could sow crops in the spring.

Working night and day, and funding their project themselves—each member of the team put in $10,000, supplemented by loans from local banks—they dug through the frost of Kansas winter nights. “We didn’t dig the boat to create a museum,” says Hawley. “It was the adventure of finding buried treasure.”

Their first discovery was splintered spokes from one of the giant paddle wheels. The vast engine boilers emerged, and the shape of the main deck gradually appeared from the earth.

There was no sign of the legendary hoard of gold and whiskey barrels. But then they reached the cargo holds below, and discovered what would be the largest time capsule of 19th-century American history.

Steamboats dominated travel in the U.S. during the 19th century. Before the advent of the railroads, steamboats pioneered the rapidly expanding Western frontier, carrying passengers and supplies along rivers such as the Mississippi and the Missouri.

A 19th-century steamboat moored at a river bank. (Photo: New York Public Library/Public Domain)

In August, 1856, the Great White Arabia was chartered for a run from St. Louis to Omaha City, Nebraska. She was carrying over 220 tons of cargo destined to help equip 16 frontier towns, including St. Joseph, Missouri and Sioux City, Iowa. She also carried 130 passengers, mostly women and children, who were traveling to meet the husbands who had forged ahead to settle the land.

Steamboat voyages were frequently hazardous, and hundreds of steamboats sank along the Missouri alone. The vast amounts of chopped wood required to fuel the steamboats meant the rivers were littered with lethal remnants of logs, known as snags. It was one such snag, hewn from a sycamore tree, that did in the Arabia.

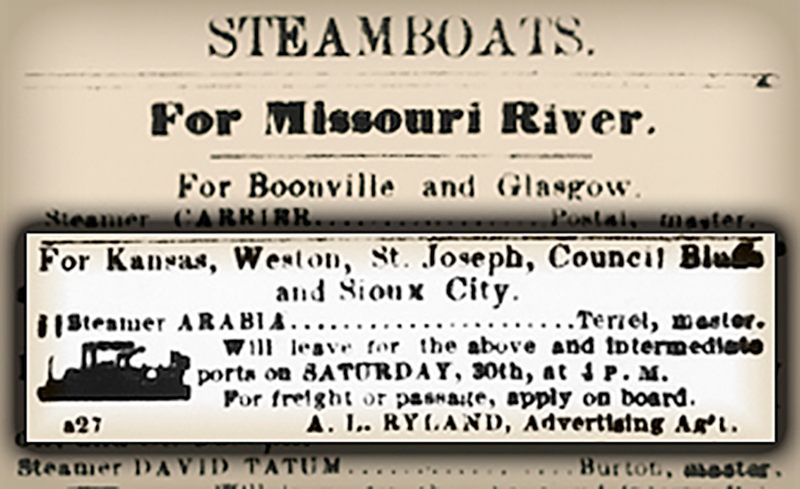

Advertisement for the Arabia’s final voyage; steamboats were used to carry both passengers and cargo. (Photo: Courtesy of the Arabia Steamboat Museum)

On September 5, 1856 about an hour north of Kansas City, the Arabia hit the sharp snag, and within minutes lay at the bottom of the Missouri River. All her passengers were saved, except for a mule, chained to a sawmill on the ground deck. But the Great White Arabia was lost, along with all her precious cargo.

A hundred and thirty years later, the exact contents of the steamboat’s cargo hold was still a mystery to Hawley and his team. It was entirely possible that there was nothing lying under the field they had so expensively begun to dig up.

But three weeks into the dig, they found the first artifact: a small rubber shoe lying on the ship’s deck. The condition was so pristine they could easily read the stamp on the sole, “Goodyear Rubber Company.”

The first artifact found, the shoe was lying on the main deck of the Arabia. (Photo: Courtesy of the Arabia Steamboat Museum)

As the cargo deck was gradually unearthed, so too was the remarkable scale of the find. “The dishes were uncovered soon after,” says Hawley. “It was the dish barrel that really gave us the encouragement that the enormous amount of money being spent might actually be worth the gamble.”

Visiting the collection of treasure rescued from the Arabia, the scope of the artifacts is staggering. The Arabia was, after all, going to be supplying everything needed for 16 outpost towns. That meant everything from axes to saddles to skillets to umbrellas. To give some indication of scale, the team found over 4,000 shoes and boots and over three million Indian trade beads.

Like walking into a pre-Civil War department store; the collections size is matched by the pristine condition of the artifacts. (Photo: Courtesy of the Arabia Steamboat Museum)

Today the collection is so vast it is housed in a former fruit market in Kansas City that the team turned into a museum. Walking inside is like stepping back in time into a well-stocked department store from just before the Civil War. And because of the peculiar nature of the moving of the Missouri River bank, the collection is mint and pristine. Crates of cognac and champagne taste just as they did in 1856. Household matches are dry enough to light the cords of still fragrant tobacco, that could still be smoked in the dozens upon dozens of preserved, delicate clay pipes.

Clay pipes survived the shipwreck, as did the tobacco to fill them. (Photo: Courtesy of the Arabia Steamboat Museum)

The collection is so big that Hawley estimates it will take another 10 years to present it all. Until then, the items waiting to be catalogued are preserved encased in ice blocks. Visiting the lab, I saw, among the artifacts being cleaned that day, a sawmill vise, cast-iron stove hinges and yet more shoes.

At the tail end of 1988, the treasure hoard of the Arabia was finally unearthed, the team working in the freezing cold. “It was like Christmas every day,” Hawley says. But as winter moved into spring, their time ran out. The diesel-fueled generators and water pumps fell silent, and the remains of the giant side-wheeler Arabia were once again buried over, ready for that year’s crops to be sown.

“We came to cherish each and every item we located, and vowed not to sell”, Hawley says, “but instead to preserve the Arabia collection … no artifacts have been sold and it’s supported only by those willing to purchase a ticket for a museum tour.”

Uncovered pistols from the Arabia; small and pocket sized, but would have provided protection at close range. (Photo: Courtesy of the Arabia Steamboat Museum)

While the Arabia lies once again dormant in the cornfield, plans are already underway for the next excavation this winter: the steamboat Malta. Operated by the American Fur Company, the Malta sank in the Missouri in 1841, headed for trade with Native Americans, and would have returned laden with expensive pelts.

“We recently completed the outlining of the Malta”, says Hawley. “That was followed up by core sampling to confirm the existence of recoverable items, and to allow us to evaluate the condition of what lies buried.”

Like the Arabia, the Malta is underground and not underwater. “The boat lies about 50 feet deep and is situated about 1,500 feet from the Missouri River,” says Hawley. It “will be recovered during the winter months to provide cold air for the collection and lessen the threat of spring and summer flooding of the river.”

“The stories of these great frontier steamers”, says Hawley, “and the heroic pilots that steered them up this uncertain river have fallen silent. It seems this amazing chapter of American history is overlooked … perhaps our efforts in retelling the Arabia’s story, and that of the steamboat Malta will pass along to a future generation a glimpse of what life was once like in a younger America.”

But just what lies in wait underneath this midwestern field remains a mystery to be uncovered this winter.