There are any number of difficult times to choose from, sure. When bills were left unpaid for months. When utilities were turned off. For a few years, Jayson Tatum would sleep in the same bed as his mother, Brandy Cole. For a time, they didn’t have any furniture at all.

But that stuff was just details—the kind of challenges and struggles you’d expect when you’re the only child of a single mom who had you at age 19. And Cole shielded her son from most of it. She was determined that—no matter what the statistics showed about teenage parents—she would become a success and he would learn from that. So she didn’t let him worry about the everyday struggles during those times.

Her goal was always to show him that they were moving toward a good life.

But one day, when Tatum was in fifth grade, there was no shielding him from reality.

Cole had moved out of her own mother’s house when Tatum was six months old because she wanted a life for the two of them. She bought a tiny two-bedroom, 900-square-foot house in St. Louis’ diverse University City. There was a postage-stamp backyard and a chain-link fence and, most importantly, a roof over their heads.

Cole picked her son up from school, and when they got home, Tatum saw a pink piece of paper taped to the front door. A notice of foreclosure.

“And she started crying,” remembers Tatum. “I didn’t know what to do. I just felt helpless. I wanted to help so bad. But I was just 11 years old.”

Tatum’s mother went inside the home, feeling she’d failed her son. For an hour, maybe two, the mother and her son swam in their sorrows.

It was the low point. Tatum, now a top prospect in the NBA draft after a dynamic freshman season at Duke, remembers it well. But not just because of the feeling of hitting rock bottom. Also because of what happened next.

Cole dried her eyes and looked at her son.

“All right,” she told him. “I’ll figure something out. I always do.”

When Tatum was in first grade, a teacher asked him what he wanted to be when he grew up.

The answer was easy. An NBA player, of course. The teacher guffawed. Pick a realistic profession, she told Tatum. Change your dreams.

“I was livid,” Cole says. “I went into the school the next day and talked to the teacher, and it wasn’t, like, a two-way conversation. I said, ‘Ma’am, with all due respect, if you ask him a question and he answers, I don’t think it’s appropriate to tell him that’s something he can’t achieve when I’m at home telling him anything he can dream is possible.’”

But their two-bedroom household wasn’t about dreaming; it was about doing.

Tatum’s mother was a couple of months away from going to college when she found out she was pregnant. Drop out? No. The single mom gave birth during spring break and was back in class the next week. Then she just brought her toddler to class with her. He kept coming to classes with his mom: undergrad, law school, business school. She’d be studying for law school with her son lying across the foot of her bed. He’d flip through her property law books. “Mom, I don’t want to ever read these kind of books,” he would say. “I want to play basketball.” “Well, you better work really hard,” she would tell him.

So he did. Every morning, he’d pop his head into his mom’s room at 5:30 a.m.: “I’m gone, Mom. I love you.” Then off to the gym, a 90-minute workout before class.

He just worked and worked and worked and worked. — Frank Bennett, Jayson Tatum’s high school coach

“I get to school about 6:30 every day, and he was here at 5:45, 6 o’clock at the latest, getting his work in,” says Frank Bennett, who coached Tatum at Chaminade Prep in St. Louis. “What’s impressive is he did it every…single…day! I remember the only day he took off. It was the day after we won state. That was his only day off.

“That is just him. He just worked and worked and worked and worked.”

Tatum’s dad remembers the moment he realized his son was a special talent. Tatum was in fifth grade and playing in a league with grown men—and he averaged 25 points per game. “The older guys were like, ‘Hold on, how old’s this kid?’” Justin Tatum laughs.

Tatum’s mom raised him, but Dad was always around. He called Tatum every day. Tatum would toddle around his dad’s locker room at Saint Louis University, listening to pregame speeches with his eyes wide. When Justin was playing professionally in the Netherlands, Mom took Tatum overseas to visit his dad. By the time Justin’s international basketball career was over, he came back to St. Louis and was one of Tatum’s primary coaches.

Since they are close in age, it was almost as much a friendship as a father-son dynamic. Justin taught his son the rappers of his generation like Jay Z, Tupac and Biggie; Tatum taught his dad which sneakers were cool these days. Once Tatum was in high school, he’d lend shoes to his dad. Tatum’s feet were one size bigger, but his dad would just wear an extra pair of socks.

But ask Tatum where his confident and mature demeanor comes from, and he’ll tell you he owes it all to his mom. At home, his mother drilled him. Tatum would be playing NBA2K in his room, and his mother would pop in and tell him to pause the game. Then she’d shove a hairbrush in his face. Mom, taking a break from her career as a lawyer dealing with policy and compliance, was the interviewer, and Jayson was the star player. She’d grill him about the video game like she was Craig Sager. “Who’s going to ask me these questions, ma?” Jayson would say. Her reply: “ESPN—when you’re one of the best players in the country.”

Soon he would be, a silky-smooth wing, consensus top-five recruit and the centerpiece of what recruiting experts called Coach K’s best-ever recruiting class.

NBA teams obsessively measure everything they can before taking the plunge and drafting a prospect. Height, height in shoes, weight, wingspan, standing reach, body fat percentage, hand length, hand width, standing vertical leap, max vertical leap, lane agility time, shuttle run, three-quarter court sprint…

But NBA scouts will tell you the most important judgments come not from the gym but from the exhaustive interviews with coaches and front-office executives, where they measure what’s between the ears. Just ask teams that drafted guys like Draymond Green and Malcolm Brogdon, Steph Curry and Gordon Hayward: Character and personality matter.

Tatum’s measurables speak for themselves. One year ago, at the Hoop Summit in Portland, he was a bit over 6’8″ with a wingspan of nearly seven feet. He’s put muscle onto his lean frame since then, and in his 29 games at Duke he proved that he can be always consistent and frequently spectacular, averaging 16.8 points and 7.3 rebounds. His shooting stats were promising for a freshman wing: 34.2 percent from three, 84.9 percent from the free-throw line.

Jeremy Brevard-USA TODAY Sports

But it’s in the intangible, between-the-ears part—the brain honed from 19 years of working toward this moment—where Tatum may shine most of all.

ESPN analyst Jay Bilas remembers seeing Tatum right before Duke’s preseason pro day in October. (The pro day was when Tatum sprained his foot, an injury that knocked him out for more than a month.) Tatum joined in a pickup game with a bunch of Duke’s former NBA players. Bilas saw a young player who was dominant: confident, intelligent, opening the eyes of these NBA veterans.

“Skill-wise he’s ridiculous—I think he’s the most talented player in the country,” Bilas says. “He’s built for basketball. Markelle Fultz may be ahead of him [on draft boards], but I believe Tatum’s more talented. He can guard multiple positions. He’s 6’8” and long. He can do more long-term than anyone in this draft.

“The hardest part is you’re not drafting for now—you’re drafting for later. And how good is Jayson going to be in three or four years? I think he’s going to be kick-ass good.”

He’s built for basketball. Markelle Fultz may be ahead of him [on draft boards], but I believe Tatum’s more talented. — ESPN analyst Jay Bilas

NBA scouts and executives may not all agree that Tatum is the most talented prospect in this stacked draft. Many will say Fultz. Others will say UCLA’s Lonzo Ball or Kansas’ Josh Jackson. But you’ll be hard-pressed to find an NBA executive who doesn’t see Tatum as a prototypical NBA body with a prototypical NBA mind.

“Tatum’s a 6’9″ point guard, point forward, whatever you want to call it,” says one Eastern Conference executive. “He’s got the ability to run an offense and create plays for others. He’s just a very cerebral player.”

In the new positionless NBA, Tatum fits. He’s got the ball-handling skills to bring the ball up the court. He’s a good outside shooter with potential to improve. He’s a natural 3, but scouts also see him as having the frame of a 4—a skilled 4-man who can space the floor but also hold his own defensively. NBA talent evaluators see a long, wiry player with a great first step and excellent offensive fundamentals.

One Western Conference executive compares him to Nicolas Batum. Other comparisons tossed out have been Harrison Barnes, Rudy Gay or Allan Houston, though his potential is a tick higher than all four of those players. A different Eastern Conference executive compares him to Ron Artest.

“But Ron Artest when he was really good—more that than a franchise-caliber piece. He’s a complementary very good player on a good team, but he doesn’t carry a bad team.”

There they are again, saying what he can’t be.

Brandy Cole did exactly what she said she would. She applied for a loan modification and at the last minute was able to save their house.

“I always was so proud that we had our own home, and he loved it here—he still does,” she says. “When you’re a kid, you shouldn’t be worried about packing up the stuff in your room and going to live with your grandma. It was a pride thing: ‘I’m going to do this. I’m not going to become a statistic.’”

That lesson—a lesson of overcoming, of putting in the work with the hope that the dividends will someday pay off—is a lesson that Tatum has internalized. He turned that lesson into the hard work and determination that’s brought him to the brink of his NBA dream. The 5 a.m. alarms. The 250 shots he put up every morning before high school. The little stuff—working on the footwork into his fadeaway, the verticality on his jump shot, the hip twist to give his offensive moves more explosion—that in a couple of weeks will make him a millionaire.

Whether it’s with the Lakers or the Celtics or the Suns or some other team that trades up to get him, he’s a surefire high lottery pick. He’ll walk across that stage, shake Adam Silver’s hand and start a new chapter in his basketball journey.

But one thing he’s certain to do is remember where he came from, and what he went through to get here. He remembers several dozen members of his extended family filling the stands at all his games. He remembers screaming his mom’s name, telling her he loved her, when she got her law school degree. He remembers all the difficulties and triumphs of a life that defied the odds.

And so when he signs that first NBA contract, Tatum and his mother have a plan. They want to start a nonprofit organization in St. Louis that supports single moms. They want to leverage Tatum’s influence, as well as the influence of other professional athletes who hail from St. Louis: Bradley Beal, Ben McLemore, Ezekiel Elliott.

They still live in that same house, but they don’t plan to sell it.

“We’ve outgrown the house 10 times over,” Cole laughs, “but he doesn’t want to sell the house.”

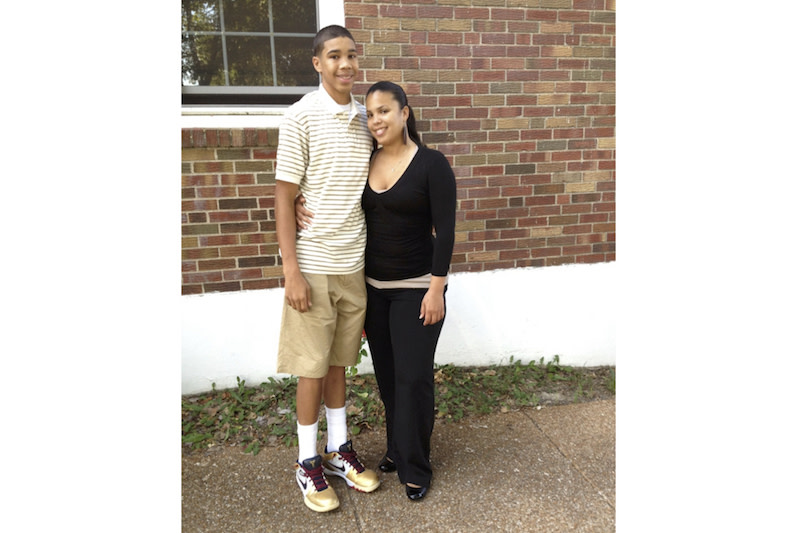

Courtesy of Brandy Cole

Instead, that house will become a transitional house for a single mom. Tatum’s mom plans to let a single mom and her child or children live there for a year, rent-free, while she gets back on her feet.

But Tatum knows, and his mom knows, that they can’t dictate the future before the future is here. So between now and June 22, they focus on the task at hand: Get better. Work hard on the fundamentals. Show NBA teams that the intangibles are as impressive as the measurables.

There are times when Tatum’s mom can’t help but flash forward.

“Sometimes I text him in the mornings and remind him how many days are left before draft day,” she says. “I mean, how many people can say there’s a finite number of days left before their dream comes true?”