Excavations in a city where Jews have lived as long as Christians yield some remarkable findings, to be displayed in a major new museum

COLOGNE, Germany — Sometime between 1267 and 1349, Samuel Bar Zelig scratched his name onto the bimah (the platform from which the cantor leads the prayer and reads the Torah) of the local synagogue.

“Apparently the children learned and played there, and evidently also fooled around,” said Michael Wiehen, a senior archaeologist with the Cologne municipality.

In the Middle Ages, synagogues were often used as classrooms. In this particular house of worship, in the heart of Europe, the children apparently climbed on chairs and table to sign their names wherever they could, Wiehen explained. “They essentially wrote something like ‘I was here.’”

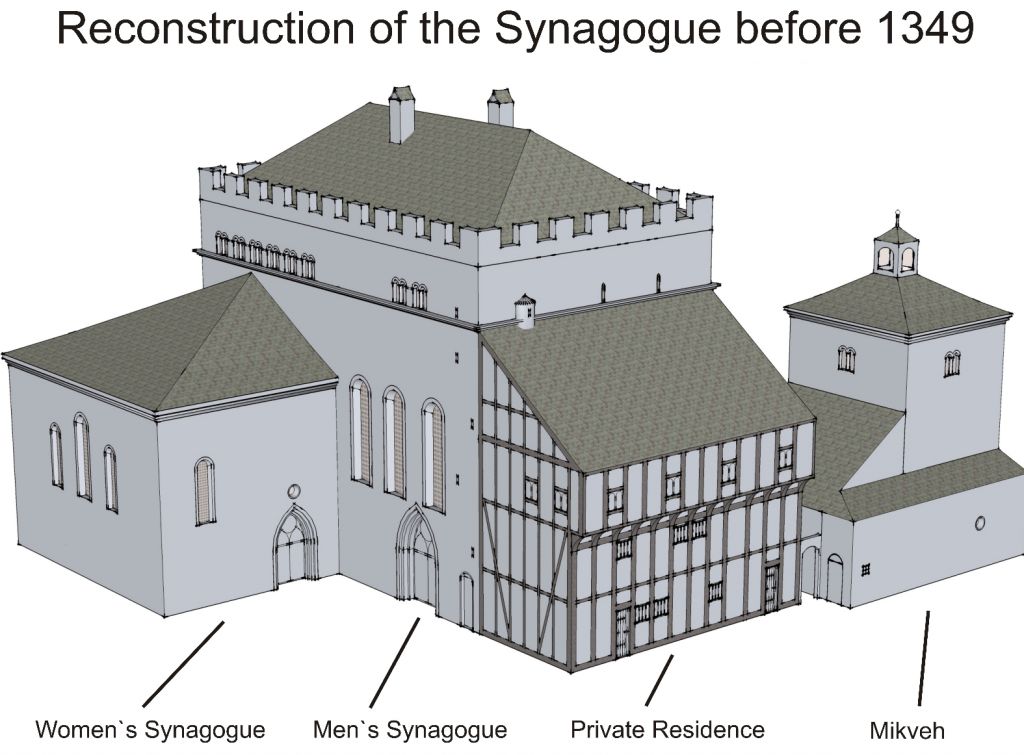

Samuel’s ancient “graffiti,” as archaeologists call this kind of scrawling, is only one of a myriad of relics that were — and are currently still being — excavated in a central Cologne square, the site of the city’s ancient synagogue. In a few years, the remaining ruins of that 700-year-old synagogue and the adjacent ancient mikveh, or ritual bath, will be visible to visitors in what promises to become one of Europe’s most fascinating museums of ancient and medieval Jewish history. Visitors will get see the base of the shul’s original bimah, and a modern reconstruction of it, in addition to many other relics found in Cologne’s medieval Jewish quarter.

More than 700 fragments of the ancient synagogue have been found, allowing the archaeologists to reconstruct the bimah. “It was probably created around 1280 by French workmen of the Cologne Cathedral lodge, which makes this Bimah a unique testimony to the cohabitation of Jews and Christians at that time,” the museum website states.

Several years in the planning, the Archaeological Zone/Jewish Museum, as the Cologne municipality calls the project, will be spread out over an area of more than 10,000 square meters (approximately 110,000 square feet). Besides the ancient shul, visitors will get to see (and learn about) ancient medallions, clay marbles and ivory dice, animal bones (which shed light on the Jews’ eating habits) and a Hebrew inscription above a private house that contained instructions about how the “feces are to be taken out.” Archaeologists also found countless slates with inscriptions, including one museum officials consider “a true historical sensation” — the oldest Yiddish writing on stone.

A reconstruction of the bimah in Cologne’s medieval synagogue. (photo credit: Cologne Municipality, Archaeological Zone: Ertan Özcan)

“We found slates that basically served as the notepads of the Jewish community before 1349,” Wiehen told The Times of Israel during a recent visit at the excavation site, where archaeologists are still digging in hopes of finding more clues on how Jews lived in the Middle Ages. “It was used to practice writing and also for literary texts, religious texts and poetry, but also for drawings and scribblings. What is possible the oldest old-Yiddish text in the world was found here.”

The slate he is referring to appears to contain a racy knight’s tale, written in an early Yiddish in Hebrew letters. “Our Jewish studies expert who’s dealing with this was exalted,” Wiehen said. “This is something truly amazing.”

The idea of another Jewish museum — an ambitious project which will cost local authorities up to €40 million, situated just meters away from the Cologne Cathedral, the city’s main landmark — had its share of controversy. The Archaeological Zone/Jewish Museum’s previous director was sent home after he publicly accused opponents of anti-Semitism. The leaders of the local Jewish community — which supports the project but insists it didn’t need it — do feel that the general public, let alone some far-right politicians, don’t like the idea of a huge Jewish museum in their city’s historic old city — especially one that demonstrates that Jews have been living in Cologne for centuries.

Indeed, Cologne is home to the oldest Jewish community north of the Alps. “Jews have probably lived in the province of Lower Germania since the end of the first century CE. By the fourth century they constituted a large and significant community,” according to the municipality.

In 321 CE — more than 650 years before the first Jews arrived in Prague — the residents of Cologne sent a letter to Emperor Constantine the Great, asking him whether they may admit Jewish residents to the town senate. Constantine said yes. (While a senate seat came with significant perks, it had to be bought with cash, hence the Christians’ interest in allowing Jews). Constantine’s 321 edict proves that Jews have lived in Cologne for more than 1,700 years — in other words, Judaism has existed in Cologne about just as long as Christianity. But where exactly the Jews lived is unclear; no archaeological evidence exists that shows a Jewish presence in the city before the ninth century, according to Marcus Trier, the director of Archaeological Zone/Jewish Museum, who also oversees the current excavations.

“That would still make Cologne the oldest proven Jewish existence in Germany,” he said. “The ninth century is still fantastically early.”

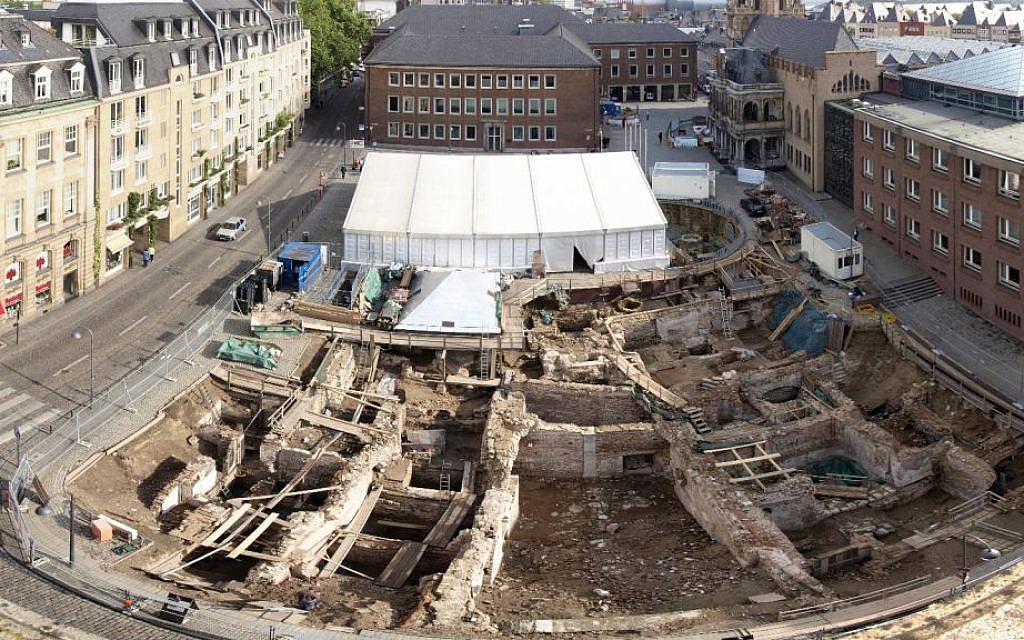

The heart of medieval Cologne’s Jewish quarter (photo credit: Cologne Municipality, Archeological Zone: Ertan Özcan)

In the Middle Ages, Cologne’s ancient synagogue stood in what was “one of the largest and even then, oldest urban Jewish Quarters,” according to the museum website. “The Carolingian Synagogue is built on a classical structure of the fourth century. An integral part of the monument is a basin that was used in a uniform manner in all subsequent phases of the building. Its 1,000-year long utilization was detected in thermoluminescence investigations. The finding could be an indicator for a synagogue that is even older.”

Excavations, smack in the middle of city’s Town Hall Square, are currently ongoing, and the public’s interest is enormous. Until recently, the municipality organized free guided tours around the site twice a week. But starting late December, as the excavation work started to wind down and the project moved toward its next stage — the actual construction of the museum — the tours ended. According to the municipality, “many thousands” of visitors have participated in such tours since the excavations started in 2007. Often too many visitors showed up for the tours so that organizers had to send home those who hadn’t signed up in advance.

A guide explaining some of the findings made at the excavation site (photo credit: Raphael Ahren/Times of Israel)

The visit, guided by art historians and archaeologists, started in a huge white dig tent, where conservation work is currently in progress on large parts of the synagogue and the surrounding buildings. The guides then lead the group to the next part of the excavations, allowing a glimpse of some of the houses and shops that made up the Jewish neighborhood, including the ruins of several buildings owned by Jews before the Black Plague pogrom of 1349.

The findings, many of which will be visible to the public, highlight the painful history of persecution, according to Trier, the museum’s director.

An earring hidden by its owners in Cologne before the 1096 pogrom (photo credit: YouTube screen grab Archaelogische Zone/Juedisches Museum)

“We have parts of synagogue furnishing that are clearly connected to burnings and destruction, to murder and total destruction of a neighborhood,” he said. Besides slates burned in the fires of the pogrom, archaeologists also dug up coins that were clearly hidden by their owners as they prepared to escape the angry mob. An ornate golden earring was hidden by its owners right before the pogrom of 1096, during the First Crusade. It was rediscovered only now and will feature prominently in the new museum.

The museum will not hide the dark sides of history, but will also show the level of peaceful coexistence that prevailed at times, Trier said. “Over many years, decades, centuries the Jewish community was a vibrant part of this city.”

The archaeologists found items that allow them to recreate many facets of Jewish life in medieval Cologne. “Significant finds rescued from the cesspit used by the rabbi’s lodging on the upper floor of the Synagogue date from a time shortly after August 1349 and give a unique insight into the way of life of a Jewish family,” the museum website states.

When the museum opens for the public — no exact date has been set yet, but the municipality estimates that it might take another few years — visitors will be able to see the actual ruins of houses where medieval Jewish families lived. More than that, they learn a great deal about the families who lived there — their names, how they lived and which professions they had.

“We found lists with names and outstanding payments from a bakery,” Wiehen, the archaeologist, said, giving just one example of the many findings shedding light on medieval Jewish life in Cologne.

One particularly interesting artifact dug up near the ancient synagogue is a stone tablet with a Hebrew inscription, which, on the outside looks like entirely ordinary. It reads: “This is the window through which the feces are to be taken out.” According to Haaretz, which first reported the finding in 2012, the tablet was “placed above a walled-up window in the cellar of Lyvermann House, which was built in about 1266 and belonged to a wealthy Jewish family that lived right near the synagogue.”

Tel Aviv University Prof. David Assaf told the paper that such “a serious-amusing inscription has never been found anywhere, not before and not since.” The inscription is also significant because it showed that Hebrew was a living language among medieval Jews, he said.

Latent anti-Semitism?

But, as it happens, nearly every project that has to do with Jews and Germany, is prone to controversy, and the Archaeological Zone/Jewish Museum Cologne is no exception. Last year, the project’s then-director, Sven Schuette, caused a storm of protest when he accused opponents of the multi-million euro project of “latent anti-Semitism.”

“They think it would be more appropriate to build a nice plaza here, rather than a Jewish museum,” Schuette told Haaretz. “They are not neo-Nazis, just foolish people who do not understand history,” Schuette said, adding that the project’s budget was “less than [the cost of] one subway station…but still there are those who say it would be preferable to build another kindergarten.”

An artist’s rendering of the Cologne Jewish Museum/Archeological Zone (photo credit: screen grab YouTube Archaeologische Zone/Juedisches Museum)

Schuette’s comments were widely discussed in Cologne’s media, and a few days later, Mayor Jürgen Roters transferred Schuette to a different position (as a civil servant he couldn’t be fired.) “Cologne residents are socially involved and open to dialogue,” Roters told Haaretz at the time, rejecting Schuette’s claims. “The debate over the museum and the archaeological site was lively from the start and included budgetary, urban and administrative aspects — but it was not at all motivated by anti-Semitism. There are small extreme right-wing groups that try from time to time to exploit the project for their propaganda purposes, but they’ve failed.”

But the plans for the museum were opposed not only by the far-right party Pro Koeln. Local politicians from the center-right CDU party (the party of Chancellor Angela Merkel) said it was “madness” for a city already in debt to spend so much money on so massive a project. “Cologne cannot allow itself to build a new museum,” leading local CDU politician Volker Meertz said.

Either way, Schuette had give up the reins, and Trier, his successor, refused to discuss the affair. “I look forward, and not behind; I lock backwards only professionally, in my work as archaeologist,” he said. Of course there were and might still be some who deem the project too expensive, but now that all contracts are signed and the controversy with the Israeli press is over, the population is “overwhelmingly in favor” of the museum, he said.

The local Jews beg to differ. Sure, the right-wing Pro-Koeln party voted against the proposal to build a Jewish museum in the city center, and so did some CDU politicians. But there were also others who didn’t love the idea. “There still is squabbling and a very low acceptance within the population,” said Abraham Lehrer, one of three chairmen of Cologne’s 5,000-member strong Jewish community. Opponents of the project like to blame the municipality’s dire financial situation, arguing that public funds are more urgently needed for social issues and need and to repair streets, Lehrer added. Do anti-Semitic resentments play a role in this? “I wouldn’t rule this out,” he said.

The Roonstrasse shul in Cologne, the city’s main synagogue (photo credit: courtesy sgk.de)

However, he stressed, people who aren’t enthusiastic about the idea of a Jewish museum near their city’s central square should not all be viewed as anti-Semites. “It’s more like a not-in-my-backyard kind of thing.” While he has never encountered anyone who objected to the museum on the grounds that it showed that Jews have been living in this city for more than a millennium and a half, there are those who feel that German postwar guilt feelings prevented the political echelon from opposing the plan, Lehrer said. There are some who claim that, 70 years after the Holocaust some politicians would vote in favor lest they be accused of wanting to “wipe the slate clean,” even if they really oppose it on financial grounds.

If the museum fulfills its expectations, it could turn Cologne into a must-see destination for tourists interested in Jewish history, he surmised. “Because this museum is not another Holocaust museum, it’s not another version of the Jewish Museum in Berlin. It will be a museum of Jewish Cologne, and with this it could a name for itself in the Jewish world.”